The London of 1888 was a very different beast to the City we know (and love?) today. Yet, in many ways, looking back at it, in old photographs at least, it is also a very familiar place.

Many buildings, particularly in Whitechapel, have long since disappeared. But many have survived and would be recognisable by any Victorian citizen who found themselves transported forward in time to the second decade of the 21st century.

For us, we can still gaze upon the crowds milling around the thoroughfares of the West End, or walking along East End arteries, such as Whitechapel Road and the upper reaches of Commercial Street, and instantly identify quite a few of the buildings.

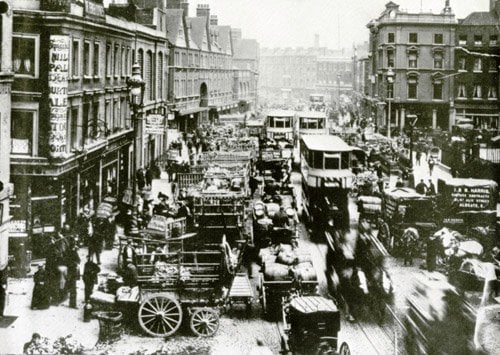

BUSY, TRAFFIC CLOGGED STREETS

What Victorian Metropolites would make of our modern traffic-clogged streets, however, is anybody’s guess.

The “clogging” bit would, no doubt, be familiar to the time-jumping 19th century inhabitant, but the types of vehicles would strike them as very different indeed.

For us, were we to go back in time, one of the biggest differences would also be the vehicular traffic on the streets.

There would have been horses everywhere, and the noise of their hooves, clip-clopping over the cobbles on the streets – not to mention the smells and “deposits” that emanated from them – would be instantly detectable, and noticeable, to our refined 21st century nostrils!

But, then again, a Victorian resident’s nostrils would, no doubt, begin twitching uncontrollably as they take in the delicate aroma of the emissions and fumes emanating from the backs of the cars, cabs, busses and trucks that edge along our modern streets, often at much slower speeds than our 19th century ancestors managed!

Fumes then, fumes now. Horses for courses, and porsches for porsches, so to speak!

THE STAR LOOKS BACK

On the 17th January 1888, a new newspaper hit the streets of London.

It was called The Star and it was one of the newspapers that would benefit enormously from the Jack the Ripper atrocities that took place later that year. Indeed, The Star quickly realised that any coverage of the Whitechapel murders would lead to a massive spike in sales, and, as a consequence, the paper devoted gallons of ink and acres of paper to coverage of the crimes.

You can, if you wish, read about how the paper benefited from the crimes in this previous article.

The Star celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 1938 and, as part of the celebrations, published its story, in the pages of which a comparison was made between the London of 1888 and the London of 1938.

A REMARKABLE DIFFERENCE

The article is interesting in that it reveals just how much the Capital – indeed, how society as a whole – had changed over the course of the fifty years of the paper’s existence.

“The difference between the London of 1888 and the one we now know,” the first paragraph of the book observed, “is as remarkable as the difference between No. 1 of “The Star” and the Jubilee Number. Both have changed, but the changes have been so gradual as to pass almost unnoticed. It needs an effort of memory to recall what they were.”

A CITY OF DARKNESS

Having set the reminiscing tone in its opening paragraph, the book went on to remind readers of the London of half a century earlier:-

“London in 1888. A city, comparatively, of darkness, its streets ill-lighted by gas, and subject in winter to the midday darkness of fogs which we called pea-soupers.

A City without a single motor vehicle, its asphalted streets resounding to the klip-klop of countless horses, drawing the omnibuses of competing companies and the hansom cabs, which were to London what the gondola is to Venice.

Even the omnibuses were different. There were no garden seats on the top deck. We got there by little ladders and sat back to back on a pair of ” Knife boards.” When the conductor rang his bell the intelligent horses settled into their collars without any word of command, and the passengers took a sporting interest in the driver’s efforts to pass the omnibus of the rival company; London General Omnibus Company versus the Road Cars with their little fluttering flags.

And everywhere, under the horses’ noses, the nimble orderly boys scuttled about on all fours, with their little scoops and brushes, trying to keep the pavement of our imperial city comparatively clean, and in wet weather failing malodorously.

A famous divine of the period, speaking on his return from a world tour said “I love London. I love the smell of its streets.”

People with more sensitive noses were less enthusiastic, but it is arguable whether in this respect we have changed for the better, from the farmyard smell of many horses to the reek of petrol fumes.

STEAM UNDERGROUND

Indoors there was, in 1888, already electric light, but little electric power, and on the Underground Railway we travelled in small compartments intended for ten passengers but at the rush hours containing as many as could be pushed into them by main force, and we travelled in a sulphurous atmosphere of smoke and steam, for all the trains were steam-drawn and dimly lit by gas.

About this, too, there were optimists, who held that the sulphur was good for people with weak lungs, and there was the Underground porter who said that he had spent his working life down there and “it never did him no harm.”

CHANGE ABOVE GROUND

Above ground the unobservant might see smaller change, and yet what differences there are.

We almost forget the gut in the Strand between the churches of St. Mary-le-Strand and St. Dunstan’s in the East.

We forget the parallel alley-way of Holywell Street where the studious could buy a second-hand copy of any book in almost any language, and the curious could furtively acquire many other things which are not sold openly.

To the north of Holywell Street were the close-packed slums about Drury Lane, where Aldwych and Kingsway now give such a fine impression of wealth and dignity and commercial activity.

LONDON HAD SHOT UPWARDS

Everywhere during these fifty years London has shot upwards.

It is still no city of skyscrapers, but, wherever old buildings have come down, new ones have risen to the full limit permitted by the Building Acts.

At Piccadilly Circus, as in the Strand, a complete transformation has taken place, and many famous and curious old buildings have disappeared on the north side, while Regent Street and the Quadrant have been completely remodelled, to the annoyance of people who do not like to admit that Queen Anne is dead.

MORE MONEY TO SPEND

A minor, but most significant, change is in the growth of the refreshment trade, which means in the habit of taking meals away from home.

In 1888 there were already a few Aerated Bread shops, but not a single Lyons teashop.

Now they are everywhere and seemingly always full.

In 1888 while there were many good shops, in London there was only one big department store, Whiteley’s. Now there are a dozen great department stores as important as Whiteley’s, and, like the refreshment houses, they are always full.

Superficially, one might say that the difference is that nowadays the people of London have more money to spend.

THE POOR WERE MUCH POORER

And this reminds me of the great change which these fifty years have seen in respect of what may be called visible misery.

In 1888 we had not heard of the submerged tenth, although Charles Booth was already far advanced in his masterly investigation of poverty.

But we had the real thing, plain to all our senses.

The poor in 1888 were poorer by far than they are today, they had fewer alleviations of their poverty.

Perhaps, too, they had less reticence concerning it.

The streets were full of beggars.

In the poorer districts barefooted children were a common sight.

And, at night, the noble river embankment was a mile and a half of sheer misery, with homeless people sleeping out in all weathers.

THE SALVATION ARMY DID THEIR BEST

The Salvation Army was doing its best.

Private but badly-organised charity did something.

But the city’s conscience had not yet been aroused to a realisation that this misery was a public concern.

In this respect it is safe to claim that there has been a marked advance since 1888.

There is still plenty of poverty, there are still plenty of those who, being willing to suffer in silence, are permitted to suffer, but, by legislation, or by municipal energy, or by private benevolence, or by all combined, the submerged tenth has been reduced to a smaller fraction, and that fraction brought nearer to a surface where life is endurable.

SUPPORT FOR THE UNDERDOG

I am not seeking to prove that “The Star” is entitled to all of the credit for this improvement, but it has, from its first number, spoken out on behalf of the under-dog.

And, before telling the story of ” The Star” itself, let me recall something of the circumstances which called it into being.

In 1888 London was governed unsatisfactorily (and that is a mild term) by local Vestries, (replaced by Borough Councils, in 1900) and, centrally, by the old and discredited Metropolitan Board of Works founded in 1855.

THE BIRTH OF THE LONDON COUNTY COUNCIL

By the Act of 1887 the London County Council was created, with greater and more exactly defined powers and duties, to replace the M.B.W., and it was one of ” The Star’s” first tasks to campaign actively in favour of a sound and progressive County Council.

How well the campaign succeeded is now a matter of history.

But there were other public matters which in the year 1887 cried aloud for reform.

London, well-to-do London, was suffering from nerves.

It dreaded rioting and disorder.

In short it feared, without sympathising with, the explosive forces which were gathering under the cloud of poverty and unemployment in many parts of the metropolis.

In June of that year Henry Mayhew (who had written so nobly of “London Labour and the London Poor”) died.

No one cared very greatly.

TERRIBLE UNEMPLOYMENT

In September a report drawn up for the Local Government Board showed that out of every hundred working then in East London, Battersea, and Deptford, 27 were out of work, and a large number of these described themselves as absolutely without means of subsistence.

There was no so-called “dole,” no unemployment insurance, in those days.

In the same districts the average earnings of the men who were in work were only 24s. 7d. per week.

In October, unemployment was so bad that demonstrations held in various parts of London led to clashes with the police.

“The police were firm.” Their only business was to break up the demonstrations.

The Local Government Board was supine. It stated that “no Government department existed which could provide employment.”

The Lord Mayor refused to receive a deputation, and when a deputation gained access to the Home Office “no definite answer was given.”

When legislation was asked for, the reply was that “Ireland blocked the way.”

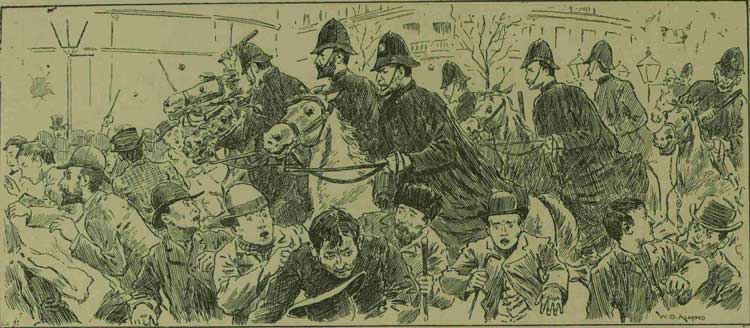

TRAFALGAR SQUARE RIOTS

And that brings me to the dramatic events immediately preceding the birth of “The Star.”

Sir Charles Warren, the Commissioner of Police, in November, 1887, issued an order forbidding any more demonstrations in Trafalgar Square, where public assembly had always been held to be a public right.

In protest against this order and against the imprisonment in Ireland of Mr. William O’Brien, M.P., a number of Metropolitan Radical and Socialist associations organised a “test meeting” for Sunday, November 13.

The meeting was prohibited, and Sir Charles Warren drew a thick black line of two thousand constables, standing four deep, completely round the square.

Between three and four o’clock the procession of demonstrators began to arrive, and the historical “Trafalgar Square Riots,” as senseless and as unnecessary as Peterloo, were “on.”

A hand-to-hand struggle to pass the cordon of police began.

The demonstrators were driven back, and two of their leaders, Mr. John Burns, later a Minister of the Crown, and Mr. R. B. Cunninghame Graham, M.P., were locked up and charged with unlawful assembly.

THE AUTHORITIES LOST THEIR HEADS

After this the authorities completely lost their heads. Mr. Marsham, the Bow Street magistrate, rode into the square on horesback and read the Riot Act.

Two squadrons of the Life Guards were called out, and, when they had difficulty in dispersing the crowds, were reinforced by a detachment of Grenadier Guards with fixed bayonets, and twenty rounds of ball cartridges in their pouches.

It was more by the moderation of the demonstrators than by the good sense of the authorities that a second and more disastrous Peterloo was avoided.

It was recorded at the time that “The cheers and good humour with which the soldiers were received were in striking contrast to the attitude of the rioters towards the mounted police,” who had ridden them down unmercifully.

So “Bloody Sunday” ended.

All this, however, was rather symptomatic of the spirit of the time than a direct cause of the foundation of “The Star” It was, however, a notable coincidence that Messrs. Burns and Cunninghame Graham were brought to trial at the Old Bailey, and each sentenced to six weeks imprisonment, on January 17th, 1888, and on that day ” The Star ” was born and reported their trial.”

SOURCE FOR THE ARTICLE

The source for this article is The Story of The Star 1888 – 1938, Fifty Years of Progress And Achievement, Part One, published by “The Star” Publications Department.