There are Jack the Ripper suspects against whom the case is so tenuous as to border on the libellous, were that suspect still alive!

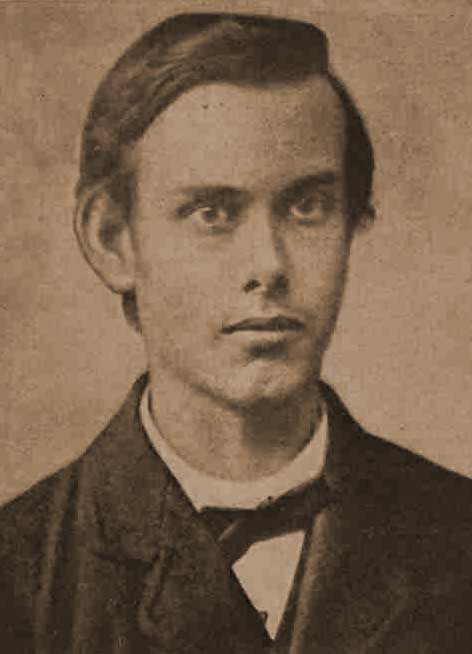

One such suspect is the poet Francis Thompson (1859 -1907).

Thompson’s poetry possesses a vibrancy and an urgency which was both applauded and condemned by the critics of the age; and reading it today one is still gripped by the depth of the imagery that his pen portrayed.

Sadly, it is the vividness of his imagery which has, largely, been used to put his name forward on the ever-expanding list of Whitechapel murders suspects.

This is such a great pity, as being connected to the Jack the Ripper crimes is what many people will now remember him for, and his poetry will, in many peoples minds, be relegated to second place, whereas he should, in fact, be lauded as one of the great Victorian poets.

THE HOUND OF HEAVEN

Take, for example, his 1893 poem, The Hound of Heaven, which essentially describes being pursued by the power of a ‘jealous’ God; a power from which it is all but impossible to escape.

No lesser person than the Bishop of London hailed it as “one of the most tremendous poems ever written,” whilst a critic called it “the most wonderful lyric in the language.”

Today, its power to move is still as gripping as it was when it was first written.

But, don’t take my word for it, listen to Richard Burton read it and enjoy the power of his words.

FRANCIS THOMPSON’S FIRST WORK

It must be said that, when Francis Thompson’s first volume was published, in 1893, critics were unsure quite what to make of it.

Typical of this mixed reception, was the following review, which appeared in, The Illustrated London News, on Saturday, 16th December, 1893:-

A NEW AND GREAT POET

“This volume of poems is likely to make a literary sensation.

One expects to see it excessively praised and excessively abused within the next few weeks, for Mr. Thompson’s manner is the great manner, and calls for neither kindness nor tolerance.

To the reviewer, he is, indeed, a new sensation, for it is so long since a volume of poetry claiming to follow the great traditions of the art has been published, and one is cloyed with the perfection of form and the quintessence of sweetness.

AN IMPASSIONED MUSE

Mr. Thompson’s muse cares nothing at all for these things; she is at once impassioned as an inspired priestess and as riotous as a bacchante.

His imagination is splendid, his diction extraordinarily rich and fervid, and the wealth of his poetical thought even extravagant.

The book has the fault of these qualities, and lacks the chastity of reticence.

REMARKABLY SERIOUS AND BEAUTIFUL

In such a poem as “A Corymbus for Autumn,” for example, the recklessness of the outpouring does not always pause to take thought for the poem’s dignity.

The whole series of poems entitled’ “In Dian’s Lap” is remarkably serious and beautiful, and it is not in them the vagaries of the young poet’s fancy are to be looked for.

One recalls no such praise of a woman, unless, perhaps, one goes back to Sir Philip Sidney and Stella.

I have mentioned Sir Philip Sidney, and I would say again that, at his best, Francis Thompson keeps the best traditions of the Elizabethans unlowered.

THE BURNING HEART OF CRASHAW

The comparison with the burning heart of Crashaw is an obvious one.

One pardons many things on his lips, as one would on lips the burning coal had cleansed.

But he will not be understanded of the common reader. He is heavy with words which are cumbrous unless he makes them classical.

THE EXUBERANCE OF THE POETRY

The very exuberance of the poetry often sets the brain to swim. It is flight, but flight gyrating in shining air, which makes the beholder’s eyes turn earthward for rest.

LUCID AND REFRESHING

But his simplicity, when one gets it, is lucid and refreshing, as in that aerially poised lyric:-

Since you have waned from us

Fairest of women!

I am a darkened cage

Song cannot hymn in.

My songs have followed you.

Like birds the Summer;

Ah! bring them back to me,

Swiftly, dear comer!

Seraphim

Her to hymn

Might leave their portals;

And at my feet learn

The harping of mortals.

THE FINEST HARMONIES

Who is insensible to this, or to “Dream Tryst,” or to “The Making of Viola” is, we may safely say, deaf to some of the finest harmonies in earth or heaven.

It is a remarkable thing that Mr. Thompson can handle the tremendous subjects he does without ever suggesting to his courage or his unfitness.”

DEATH OF MR. FRANCIS THOMPSON

A measure of the esteem in which Thompson was held by his contemporaries can be gleaned from the glowing obituaries of him which appeared in the newspapers following his death from Tuberculosis on 13th November, 1907.

The Morning Post, reported his death in its edition of Thursday, 19th November, 1907:-

“We much regret to announce that Mr. Francis Thompson died on the 13th inst. from tuberculosis at a nursing home in London.

He only published three volumes of verse, and yet (perhaps in connection with that very cautious restraint) many modern lovers and critics of verse – and these among the first – are inclined to place him with the greatest of English lyrical poets; indeed, one such has recorded his belief that there is but one poet with whom the author of “Her Portrait “can be compared for orchestral majesty in song, and that one Milton.

“In all sobriety,” another critic of the first rank has written, “do we believe him of all poets to be the most celestial of vision, the most august in faculty.”

THE LIFE OF FRANCIS THOMPSON

Francis Thompson was born in 1860 at Ashton, in Lancashire; he was the son of a well-known and highly respected physician, and a nephew of that Mr. Edward Thompson, who was one of the group of Oxford converts who were personal friends of Manning.

On Francis’s father following his brother’s example, the boy was sent to Ushaw College, where he remained for five years.

HE FOLLOWED HIS OWN BENT

The curriculum was loosely textured, Francis Thompson was allowed to follow his own bent, far more than would now be the case, and it was while at Ushaw that he first made the intimate acquaintance with the classics which was later to stand him in such good stead.

STUDIED MEDICINE

From school he went to Owen’s College, Manchester, with the intention of pursuing his father’s profession, but already his intense love of literature had mastered him to the exclusion of all else, and he very soon found that he was mort fitted to undertake the anatomy of the soul than that of the body.

FIVE GRIM YEARS IN LONDON

He came to London, and there followed five years of brave but grim struggle to gain a livelihood; to these five years his readers can find a noble and pathetic reference in the second of his published volumes, “Sister Songs.”

HIS FIRST BOOK

Then, the sending by him of a chance poem to a magazine, entitled Merrie England, founded and edited by Mr. Wilfrid Meyncll, introduced him to the two helpful enthusiastic friends, Wilfrid and Alice Meynell, to whom dedicated his first book – that entitled simply “Poems.”

This appeared in 1893, and at once made a profound impression, being hailed with enthusiasm by critics, not least, Mr. Coventry Patmore, who introduced the new poet to a wider world of readers in an eloquent eulogium, published the Fortnightly Review.

The volume soon went through ten editions.

MORE POETRY FOLLOWED

It was followed two years later by “Sister Songs,” and then, in 1897, by “New Poems.”

Mr. Francis Thompson possessed a singularly shy and illusive personality; and he ever lived a life curiously aloof from that of other human beings.

HIS HAPPIEST TIMES

He was happiest when dwelling in the shadow of some great religious house, such as the Capuchin Monastery at Tanlasapt, or, more recently, at Storrington.

Two years ago he broke his long silence and published a quaint Treatise on Health and Holiness, with a preface by Father Tyrrell.

A PASSION FOR CRICKET

In the very brief account of him which appears in Who’s Who, and which contains no biographical details concerning his early life, his recreation is noted as having been that of cricket.

The poet was far too frail a human being ever to have held a bat, but he took a singular interest in the game, and among the papers he has left are the more notable scores of the last thirty years carefully cut out from The Morning Post.

WORLDWIDE FAME

The fame of Francis Thompson was not confined his own country: he had fervent admirers in France and in Italy, and his verse was perhaps even better known in America than in England.”

FRANCIS THOMPSON REMEMBERED

On Saturday, 23rd November, 1907, The Globe looked back on his life, and re-published some of his works:-

“That we have lost a great poet in Francis Thompson is already acknowledged by weighty pens, and I have no doubt that the sense of this loss will become much wider.

Those who know his poetry have no difficulty whatever in numbering it among the distinct stepping stones in our literature from Milton downwards.

There are things in “Sister Songs,” the “Anthem of Earth,” and “The Hound of Heaven” which the world will not willingly let die, and I hope that before long the three slender volumes will be combined in one, with a suitable memoir.

OLD “ACADEMY” DAYS

Among the materials for a biography of Francis Thompson must be numbered the admirable sketch of him contributed to this week’s “Academy” by Mr. Wilfred Scawen Blunt.

It is fitting that the “Academy ” should print, a worthy tribute to Thompson, because he was many years a contributor to its pages under the editorship of Mr. Lewis Hind.

As a member of the “Academy ” staff in those years, I met Francis Thompson frequently.

Mr. Blunt speaks of an occasional review in the “Academy” or the “Athenaeum” as all that, Thompson contributed to the world of letters after 1897.

This is hardly correct.

Thompson’s contributions between 1897 and 1901 were very numerous.

Sometimes we printed articles by him week after week, and a few of these were signed.

He was an admirable reviewer, though only in a few sudden gleams did his prose suggest his poetry.

THE NEW GRUB-STREET

Mr. Blunt shows more light than any other obituarist on Francis Thompson’s terrible five years in London before he was discovered by Mr. and Mrs. Meynell, and lifted into such comparative comfort as his health and eccentricities would permit.

Of those years Thompson did not care to talk, but Mr. Blunt tells us clearly what was dimly known.

Thompson needed about elevenpence a day to live, and he earned it “by such half-mendicancy as the English law allows, the sale of matches in the streets, attendance at theatre doors at night as a caller of cabs and casual messenger.”

Yet Thompson’s poetry embalms one picture of these forlorn days.

A little child had given him a coin in the street on her own sweet impulse, and he introduced the incident into ins “Sister Songs.”

THE POET AND THE CHILD

Here, then, is his picture of the utter darkness of the new Grub-street, shot with a ray of sunshine :-

Once – in that nightmare-time which still doth haunt

My dreams, a grim, unbidden visitant

Forlorn, and faint, and stark,

I had endured through watches of the dark

The abashed inquisition of each star,

Yea, was the outcast mark

Of all whose heavenly passers’ scrutiny;

Stood bound and helplessly

For time to shoot his barbed minutes at me;

Suffered the trampling hoof of every hour

In night’s slow-wheeled car;

Until the tardy dawn dragged me at length

From under those dread wheels; and, bled of strength,

I waited the inevitable last.

Then there came past

A child; like thee, a spring-flower; but a flower Fallen from the budded coronal of spring,

And through the city – streets blown withering. She passed – 0 brave, sad, lovingest, tender thing!

And of her own scant pittance did she give,

That I might eat and live:

Then fled, a swift and trackless fugitive.

A HAPPIER MAN

In the years in which I knew him, Francis Thompson was a happier man.

Pursued by ailment and disease, he yet responded to the mild and intermittent discipline of his “Academy” work.

His appearances at the office in Chancery-lane, though maddeningly irregular, were always cheerful; and in a long talk on literary subjects, he forgot all his troubles.

I cannot here do any sort of justice to Thompson as a confrere and a talker.

His literary information, controlled at every point by fastidious taste, was inexhaustible.

Intellectual sweetness was the note of his mind.”

A POET NOT A PERPETRATOR

There is next to no physical evidence to link the name of Francis Thompson to the crimes of Jack the Ripper, and the case against him rests largely on misportraying and misunderstanding his lyrics.

However, even in this respect, the case against him is extremely selective in the evidence used to further his candidacy.

So, let us applaud Francis Thompson for what he was, a first-rate and talented poet, and let’s forget that he ever found himself on the list of names of those suspected as perpetrators of one of the most infamous series of murders in true crime history.